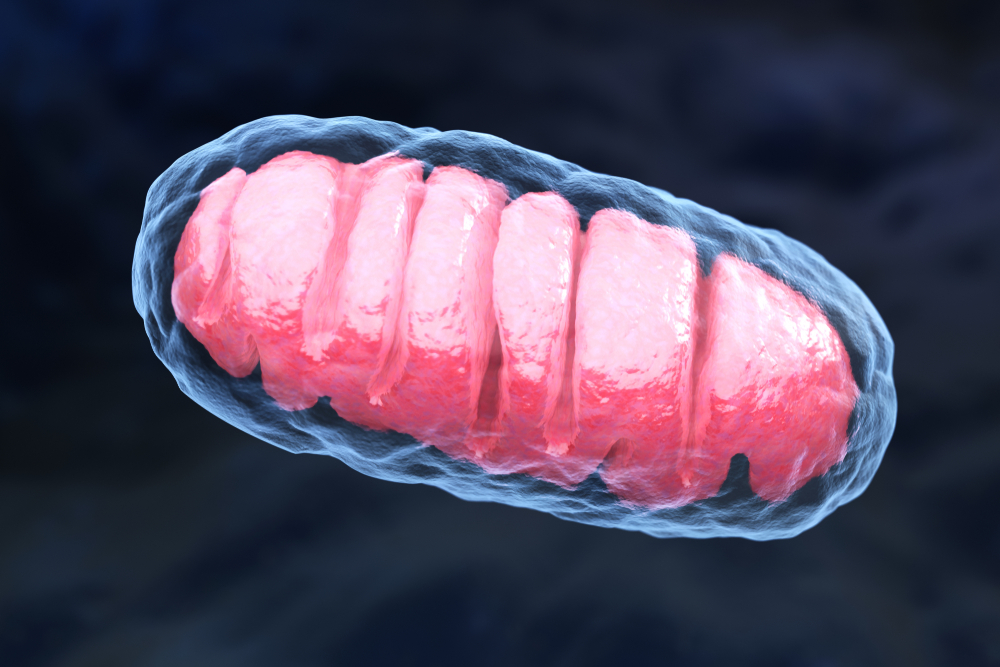

Mitochondria Transplant Could Someday Be Viable Treatment Option, Study Shows

Transplanting mitochondria — the cell compartments responsible for the production of energy in our body — from healthy skeletal muscle cells provides a short-term energy boost in heart cells, a study has found.

These findings suggest that mitochondria transplants could one day be used therapeutically to treat mitochondrial diseases, heart disease, certain neurological disorders, and even cancer.

The study, “Bioenergetics Consequences of Mitochondrial Transplantation in Cardiomyocytes,” was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

The study, led by investigators at the University of California, Irvine (UCI), is not the first exploring the idea of transplanting mitochondria to boost the energy of heart cells to improve their function. Previous studies have attempted to use this type of transplant to treat patients with advanced forms of heart disease. However, none of them focused on investigating the mechanisms underlying the potential benefits of transferring mitochondria from one cell to another.

“Mitochondria are the engines that drive many activities performed by our cells,” Paria Ali Pour, a PhD student in biomedical engineering at UCI, and first author of the study, said in a press release. “If these organelles are mutated or deemed dysfunctional, the clinical manifestations are devastating, so we decided to study the intracellular consequences of mitochondrial transplantation, and determine whether it would be a viable method for mitigating these adverse situations and helping patients.”

Researchers first isolated mitochondria from different sources, including rat skeletal muscle cells, rat heart cells, and human retina cells. The retina is the thin layer of nerve cells that form the back of the eye and enable us to see.

After isolating mitochondria from these different types of cells, the team insert them into rat heart cells, creating three different scenarios: one in which mitochondria were harvested and inserted into the same type of cell, mimicking an autologous transplant; another in which mitochondria were isolated and inserted into different cell types from the same species, mimicking a non-autologous transplant; and finally one in which mitochondria were isolated and inserted into different cell types from various animal species, mimicking an inter-species transplant.

Researchers found that regardless of where they had been harvested from, transplanted mitochondria successfully adapted to their new host cell, indicating that all different types of mitochondria transplants were feasible.

Then, researchers performed a series of metabolic measurements to evaluate mitochondria function inside their new host cell, including oxygen consumption rate and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, at two, seven, 14, and 28 days after the transplant (non-autologous transplant scenario). ATP is a small molecule used as “fuel” (energy) by all cells in the body.

Compared with untreated heart cells (controls), those in which investigators had inserted mitochondria harvested from healthy skeletal muscle cells had a significant boost of ATP production. This energy boost was apparent two days after the transplant, but the boost was short-lived, as the values quickly returned to a normal range afterward.

“Although these enhancements were short‐lived in normal cells, it is evident that there were also no adverse effects attributable to the transplantation, given that the transplant cells were doing as well as the control cells in the long term,” the researchers wrote.

They noted that further studies are needed to assess if these outcomes could be different in host cells containing dysfunctional mitochondria.

They are also planning to study the interaction of transplanted mitochondria with the host’s cell nucleus, and to monitor their function and behavior for longer periods of time inside their new host cell.

“We took a very cautious and fundamental approach with this project, because these cellular procedures, as a potential biotherapy, can have unknown and possibly grave consequences,” said Arash Kheradvar, MD, PhD, professor of biomedical engineering and medicine at UCI, and lead author of the study.

“We didn’t want to rush into human experimentation without knowing all of the potential ramifications in terms of safety and efficacy. Although we have a few hypotheses, nobody firmly knows what’s happening when these mitochondria are introduced inside the cell — or whether there will be side effects. There are a lot of unanswered questions that need to be addressed,” Kheradvar added.