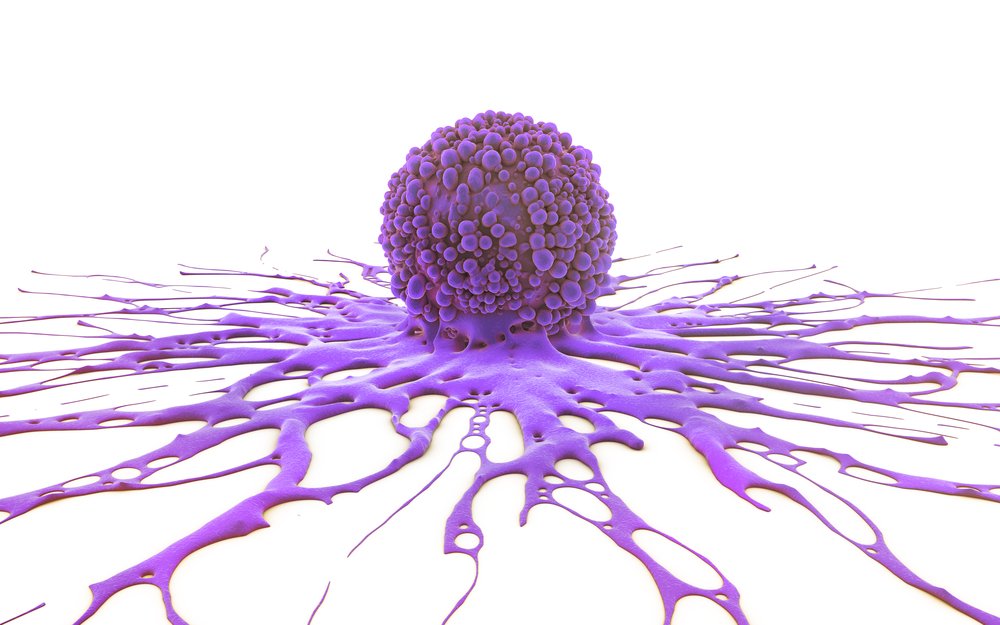

Mitochondria May Support Cancer Cell Survival, Study Shows

Researchers at McGill University in Canada discovered how mitochondria may support cancer cells’ survival even during periods of nutrient starvation. The finding puts mitochondria in the spotlight as regulators of cells’ fate and suggests that therapies targeting mitochondria can aid anti-cancer strategies.

The study “mTOR Controls Mitochondrial Dynamics and Cell Survival via MTFP1” was published in the journal Molecular Cell.

The protein mTOR, short for Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin, regulates how our cells grow in size, but also cells’ mass and numbers. Its key regulatory functions make mTOR a master regulator of cell growth and metabolism.

Work developed by McGill professor Nahum Sonenberg, PhD, and his team found that mTOR also is capable of regulating protein expression in all human cells. Particularly, mTOR targets the production (synthesis) of proteins that have as their final destination the mitochondria – cells’ powerhouses.

Now, in collaboration with McGill scientists Heidi McBride and John Bergeron, Sonenberg’s team found that mTOR also regulates the expression of proteins that can change both the structure and function of mitochondria, which ultimately protect cells from dying.

The work by Masahiro Morita and Julien Prudent, two postdoctoral researchers at Sonenberg’s lab and the study’s first joint authors, went on to show that mitochondria probably are the factors supporting cancer cells survival and inhibiting cell death by fusing together. Mitochondria dynamics underlie the cells’ fate – they fuse together leading to hyperfused mitochondria that, in this state, support cell survival. Preventing mitochondria’s fusion ultimately leads to cells’ death.

mTOR signaling is hyper-activated in many cancers, which explains why potential cancer therapy relies on inhibition of mTOR activity. In fact, several clinical trials are currently testing drugs that target the mTOR as potential cancer therapies. But, despite cancer cells no longer growing, many of them continue to survive, even in conditions of nutrient deprivation.

These findings show how mitochondria can control cells’ fate and suggest that combination therapies that reverse the mitochondria protective effects may be beneficial for cancer therapeutics.

Morita is currently at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and Prudent is now leading his own group of research at the MRC Mitochondrial Biology Unit at University of Cambridge, U.K.