World’s First Baby Born from In Vitro Fertilization Technique Using 3 DNAs

The first baby with DNA from three people has been born, representing a novel step in in vitro fertilization procedures.

The technique allows parents with a rare genetic mutation to have healthy babies, but has gained controversy because the newborn has the genetic material of two females and one male.

The now 6-month old boy’s mother carries genes for Leigh syndrome, a fatal disorder that affects the developing nervous system. The disease genes are within the DNA in mitochondria, the organelles that provide energy to cells. The mitochondrial DNA is passed to us only by mothers, so if the mother carries a mutation in her mitochondrial DNA, her babies may suffer from a variety of life-threatening conditions.

The married couple in question had already lost two older children to Leigh syndrome.

The couple sought out the help of Dr. John Zhang and his team at the New Hope Fertility Center in New York City. The team performed the treatment in Mexico, because the rules for human embryo manipulation are less restrictive than in the United States where the experimental procedure is not allowed.

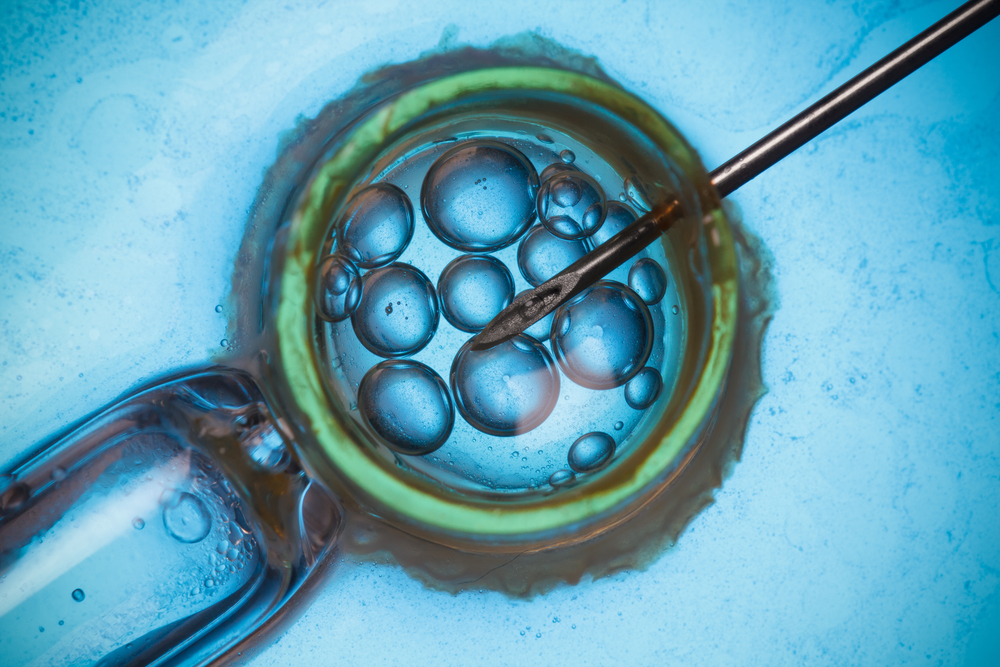

Zhang used a technique called spindle nuclear transfer. Here’s how the procedure works and prevented the transmission of the mother’s mutated mitochondria genes.

Zhang and his team performed in vitro fertilization using the father’s sperm to fertilize two eggs – one from the mother and another from a healthy donor. Before the fertilized eggs started to divide into early-stage embryos, they removed the nucleus (which is where the genetic information is located) from the donor’s egg and replaced it by the nucleus from the mother’s fertilized egg. In the end, the egg that would generate the new baby had both the DNA from the mother and father (nuclear DNA) and the mitochondrial DNA from the healthy donor.

The technique was performed in five eggs, but only one of the eggs carried the normal number of chromosomes, a key step for the normal development of the embryo. The egg with the normal amount of chromosomes was then implanted in the mother. The child was born nine months later.

Zhang tested the boy’s mitochondria DNA and confirmed that less than 1% carries the mutation. According to estimates, at least 18% of mitochondria DNA have to be affected to cause problems. Hence, 1% is hopefully too low to generate disorders.

However, as Dr. Bert Smeets at Maastricht University in the Netherlands noted, the baby will require monitoring to assess if the mutation levels remain low. There is also a chance that defective mitochondria might actually be better at replicating.

“We need to wait for more births, and to carefully judge them,” Smeets said in a press release.