New Way of Replacing Mitochondria in Embryos Seen as Effective and Safe, Awaits Approval in UK

The Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Disease has published strong evidence supporting a new in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedure that allows for mitochondrial replacement — lowering the risk of babies being born with inherited mitochondrial mutations. The findings, reported in the journal Nature, represent a huge step forward for research into mitochondrial transfer techniques, and raise hopes for people wishing to have a child not affected by the mitochondrial disease they carry.

Researchers have already begun the process of requesting the technique be approved for clinical use in the U.K.

“This study using normal human eggs is a major advance in our work towards preventing transmission of mitochondrial DNA disease. The key message is that we have found no evidence the technique is unsafe,” Professor Doug Turnbull, director of the Centre for Mitochondrial Research and a study co-author, said in a press release. “Embryos created by this technique have all the characteristics to lead to a pregnancy.”

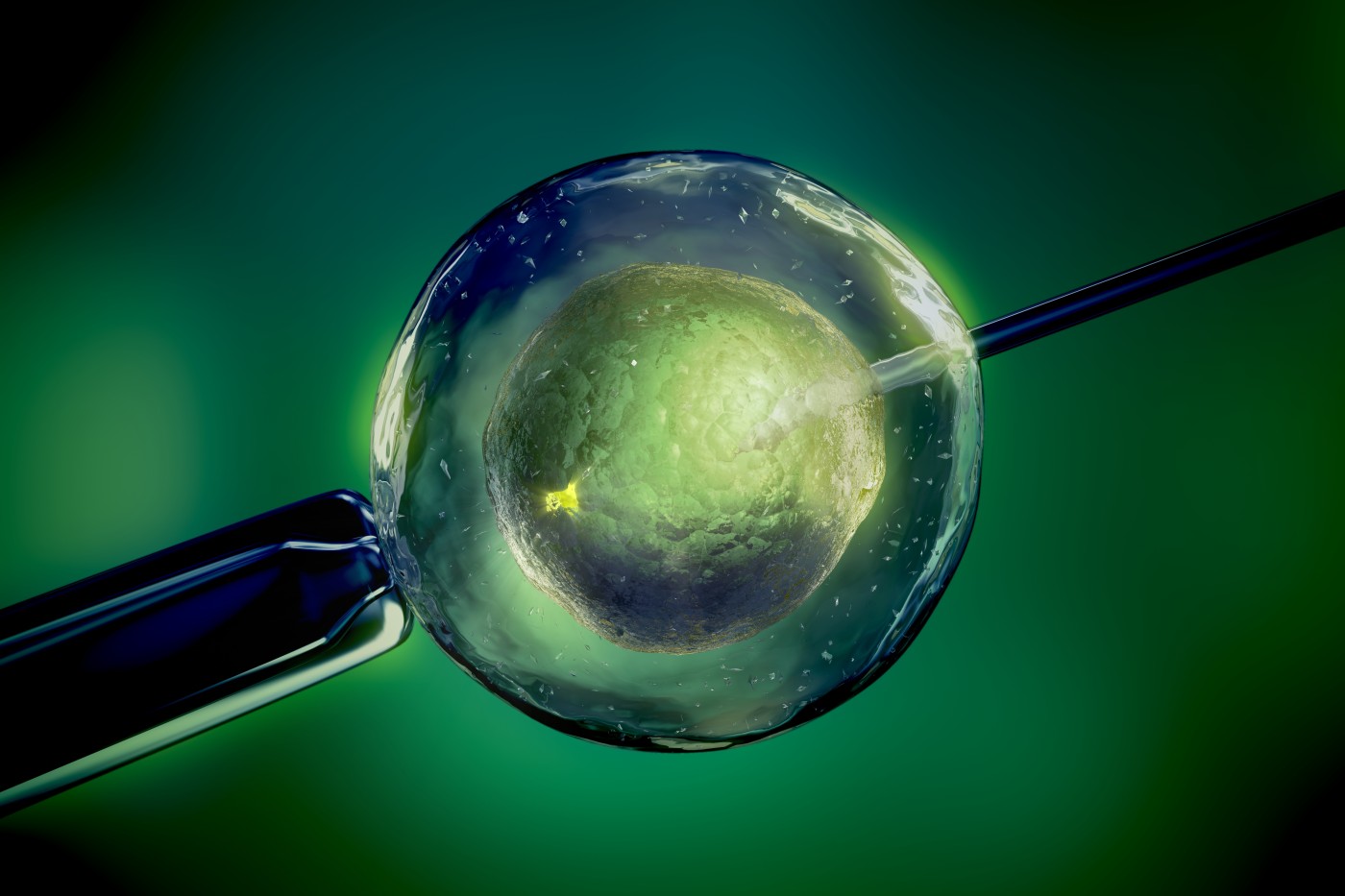

The procedure, called early pronuclear transfer, combines parts of two egg cells. A donated egg cell from a healthy individual is stripped of its nuclear DNA before being replaced with the DNA from a fertilized egg of a woman at risk of having children with mitochondrial disease.

Earlier attempts with mitochondrial replacement in unfertilized egg cells were troubled by problems such as abnormal fertilization. In this study, “Towards clinical application of pronuclear transfer to prevent mitochondrial DNA disease,” researchers attempted a new technique, transferring the DNA from already fertilized eggs. The transfer is done on the day of the fertilization, and the method showed improved survival compared to earlier attempts.

Studying 500 eggs from 64 donor women gave the Wellcome team at Newcastle University plenty of material from which to draw firm conclusions. Together with researchers at the University of Oxford and the Francis Crick Institute — all in the U.K. — the team examined thousands of genes along with other early embryo characteristics, finding no differences between experimental and normal embryos. There was also no increase in abnormalities that could lead to birth defects.

“Having overcome significant technical and biological challenges, we are optimistic that the technique we have developed will offer affected women the possibility of reducing the risk of transmitting mitochondrial DNA disease to their children,” said Professor Mary Herbert, the study’s senior author.

The study also addressed an important issue with mitochondrial replacement — the risk that diseased mitochondria are inadvertently transferred along with the nuclear DNA. Earlier studies raised the possibility that a small number of mutated mitochondria could, in some cases, increase in numbers and again cause disease, a problem recently reported in Mitochondrial Disease News.

With a mutated mitochondria carryover rate of less than 2 percent, this study showed a minimal risk that diseased mitochondria would continue to thrive in the new embryo — and possibly increase in numbers enough to cause disease.

“Our studies on stem cells does express a cautionary note that it might not be 100 percent efficient in preventing transmission, but for many women who carry these mutations the risk is far less than conceiving naturally,” Professor Turnbull said.

In fact, the team believes the new technique is refined enough to benefit patients, and the study is now under evaluation by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) Expert Scientific Panel, which will decide if the technique is ready for the clinic.

If the HFEA supports the method, the Newcastle Fertility Centre will apply to the Scientific Panel for a license to offer pronuclear transfer to women at high risk of having children affected by mitochondrial disease.

Researchers are now working to improve the method to further lower the risk of transmitting mitochondrial disease via transfer of lingering mutated mitochondria. They also need to secure funding to be able to offer the treatment at the clinic, should it be approved.

“This study adds to the extensive body of evidence built up over the past ten years suggesting that mitochondrial replacement therapy is not unsafe,” said Dr. Beth Thompson, senior policy adviser at the Wellcome Trust. “The results bring the U.K. closer to being able to offer mitochondrial replacement technique to couples affected by mitochondrial disease. The U.K.’s strong regulatory system will now kick in to decide whether there is enough evidence that this technique is safe enough to be a good choice for families.”

“I would also like to thank the women who donated eggs for this research,” added Dr. Herbert. “It would not have been possible to do this work without their help.”