Gene Discovery in Fruit Fly Study May Help Uncover Treatments for Mitochondrial Disease in People

Scientists have discovered that the tam gene can be targeted to reverse the symptoms of harmful mutations in mitochondrial genes in a fruit fly study, a finding that may uncover therapies to treat mitochondrial diseases in people.

The study, “A Genome-wide Screen Reveals that Reducing Mitochondrial DNA Polymerase Can Promote Elimination of Deleterious Mitochondrial Mutations” was published in the journal Current Biology.

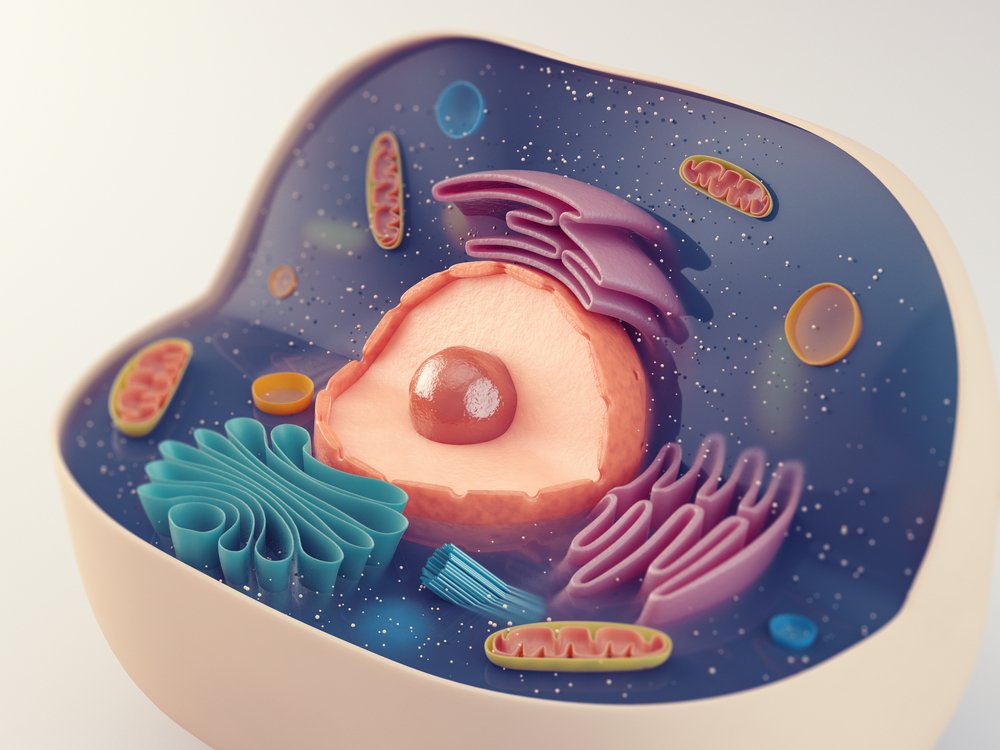

Mitochondria produce most of the energy for cellular functions. These organelles have their own DNA (mtDNA), which is essential for the expression of 13 proteins with a key role in energy production.

The mtDNA exists separately from the DNA found in the nucleus of a cell (the nuclear DNA). Half of an organism’s nuclear DNA comes from the sperm and the other half from the egg. However, mtDNA comes only from the maternal egg.

Most cells have several mitochondria inside, and the mitochondria themselves can have multiple copies of their mtDNA. However, during an organism’s development and aging process, gene mutations can occur in some of the mtDNA copies and create a mixture of healthy and mutated mtDNA copies, which compete against each other for abundance.

Some of these mutations can be harmful, and if more than 60%–80% of mtDNA copies carry harmful mutations, the cell starts to lack enough energy to support its normal processes. At this point, the person may start to experience symptoms of mitochondrial disease. If present in the egg, the harmful mtDNA can be passed down to the next generation.

So far, more than 350 mtDNA mutations are known to cause different mitochondrial diseases. The competition between healthy and mutated mtDNA copies is a key process in the development of the disease and could be influenced by genes in the nuclear DNA. However, the mechanisms behind this are not well-understood yet.

To try to better understand these processes, investigators at the Wellcome Trust/ Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute, University of Cambridge, have created a model of mitochondrial disease in the fruit fly to study changes in the abundance of mutated mtDNA over time and generations.

The researchers created what they call “three-parent flies” by taking fertilized fly eggs that already carried nuclear DNA and mtDNA from their original parents, and then added mtDNA from a “second mother.”

This way, the flies that hatched from these eggs carried two competing sets of mtDNA, one healthy and one mutated, from their two mothers, and both sets can be passed on to the next generations.

The team then did a genetic screening to measure the influence of individual nuclear genes on the competition between healthy and mutated mtDNA.

Data showed that a number of nuclear genes could limit the proliferation of harmful mtDNA and its transmission to the next generation. One of these genes is called tam and encodes a key component of an enzyme known as mtDNA polymerase, which is responsible for the production of new mtDNA copies.

The researchers found that by lowering the amount of Tam protein, the percentage of healthy mtDNA increased from 20% to 75% in one generation. With this increase, the new flies were much healthier and did not have disease symptoms.

“Tam could be a key factor limiting replication in unfit mitochondria when it falls below a certain threshold,” the researchers wrote.

The data show the “potency of the nuclear [DNA] influence on the success of mitochondrial genomes” as a factor that affects the transmission of more than one type of mtDNA during development and across generations, they added.

By changing the activity of a nuclear gene, the scientists showed that harmful mtDNA mutations could be nearly eliminated and potentially reverse mitochondrial disease symptoms.

“To achieve this dramatic change in the proportion of healthy mitochondrial DNA, we’re not changing an individual’s nuclear DNA,” Hansong Ma, PhD, the study’s lead author and group leader at the Gurdon Institute, said in a press release.

“All we are doing is reducing how much of certain proteins is produced,” she said. “This could be achieved using drugs. Our fruit flies will help us rapidly screen potential drugs compounds.”