Older Moms More Likely to Pass Along Mitochondrial DNA with Mutations, Study Finds

A mathematical model that can predict the nature of the mitochondrial DNA a child will inherit from its mother was part of a study that also found that maternal age counts in mitochondrial health, too.

This part of the study, in mice, showed that the older the mother, the higher is the risk that mutated, disease-causing mitochondrial DNA will be passed along to offspring.

The study, “Large-scale genetic analysis reveals mammalian mtDNA heteroplasmy dynamics and variance increase through lifetimes and generations,” was published in the journal Nature Communications.

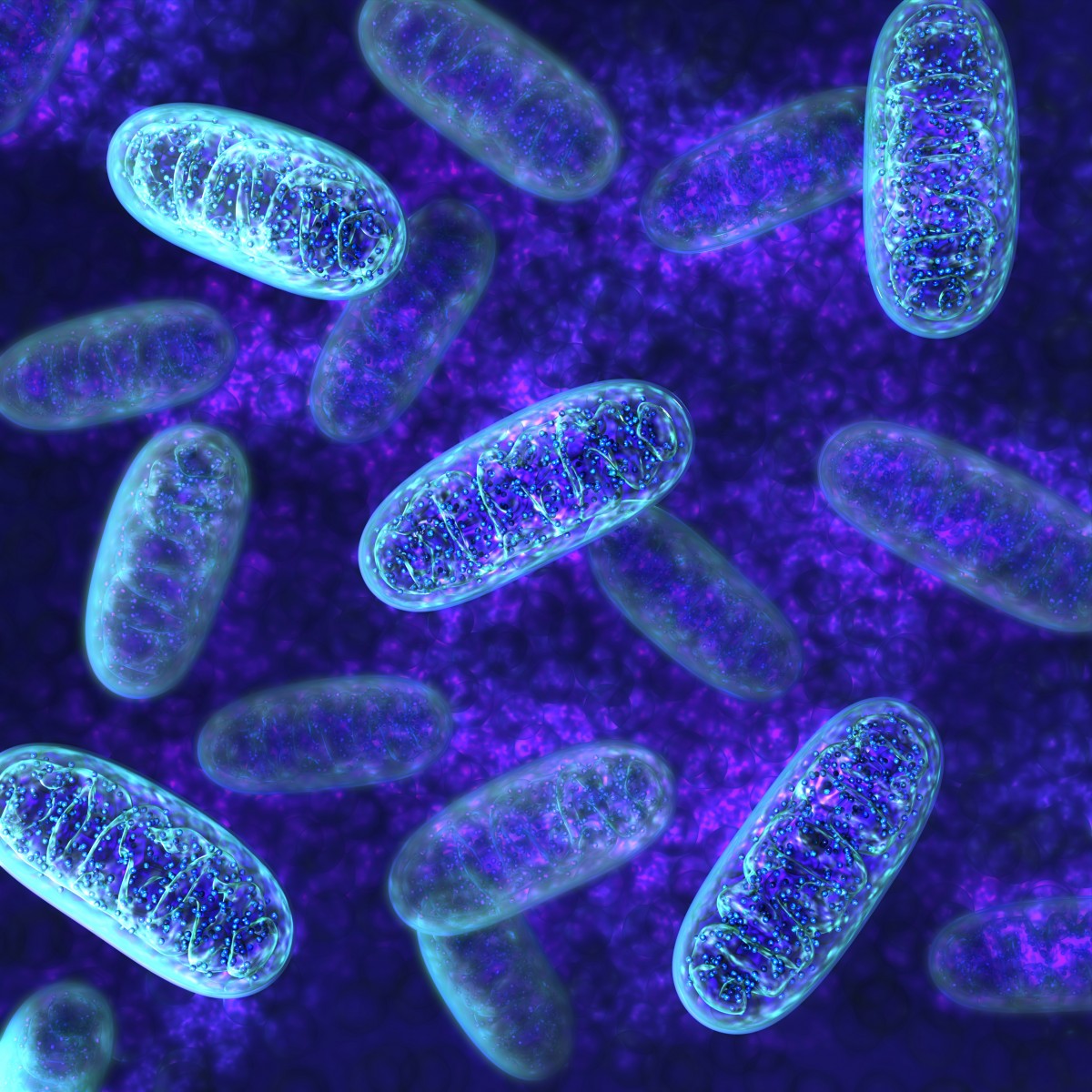

Most cells have multiple mitochondria, which house the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) — an integral component of the cell’s energy-producing machine.

mtDNA can acquire mutations over time, which can lead to different mtDNA sequences within different mitochondria of the same cell. This phenomenon, called heteroplasmy, occurs when a cell has some mitochondria with a mutation in its mtDNA and some that does not.

Heteroplasmy can influence the inheritance and onset of serious mitochondrial diseases, which develop due to mutations in key mitochondrial genes.

People inherit their mitochondria from their mothers. If the mother has heteroplasmy, it can be difficult to determine how this will affect an unborn child.

In particular, scientists don’t know how heteroplasmy changes over time in women, and whether the risk of transmitting a disease-carrying mitochondrial mutation increases or decreases.

Researchers in Europe analyzed mtDNA segregation in two mouse lines with heteroplasmy, using mothers with a range of ages. Measurements were then taken from 1,947 oocytes [immature egg cells] and 899 pups.

Using this extensive data, they were able to create a mathematical model that was descriptive of mtDNA inheritance — they transfer of mitochondrial DNA from mother to offspring, taking maternal age into account.

“Moving forward, we’re aiming to harness these powerful ways of using large datasets to describe and predict the dynamics of mtDNA inheritance in humans, and to learn what it is about these mtDNA types that predicts their evolution across generations,” Iain Johnston with the University of Birmingham’s School of Biosciences said in a press release.

Interestingly, researchers found that the heteroplasmy variance — or the variability of mtDNA — dramatically increased with increases in a mother’s age.

“We find that mtDNA heteroplasmy variance in oocytes and offspring increases linearly with maternal age,” they wrote. This suggests that the child with an older mother is more likely to inherit mutated mtDNA.

Next, the researchers showed that some mtDNA types are actually favored in inheritance over others. This allowed the team to develop a tool that can predict the risk of a child inheriting mutated mtDNA given maternal age — a tool with a potential clinical application.

“It’s this combination of a mathematical model with an unprecedented volume of experimental data that allowed us to reveal the subtle mechanisms affecting mtDNA inheritance,” said Nick Jones with Imperial College London, a co-lead study author.

“Our findings provide new insights into mtDNA inheritance and disease manifestation, which may be leveraged to optimise human reproductive techniques,” the study concludes.