Ban on Designer Babies Also Stymies Testing for Mitochondrial Disease Therapies

A federal spending bill in 2015 banned the human testing of gene-editing techniques that could lead to the “production” of genetically modified babies. But it also included two critical sentences that may have had unwanted consequences.

The legislation, which is up for renewal this year, includes a technique with promising features that could help future mothers avoid passing certain genetic diseases to their offspring.

It clearly references the use of such techniques to modify the human germline, experiments that several scientists consider “irresponsible” at this point because of the impossibility to predict potential outcomes.

But regulators decided the description also applies to mitochondrial replacement therapy, which entails taking the nucleus out of a human egg and transplanting it into an egg from another person. This technique has been used to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial disorders to children.

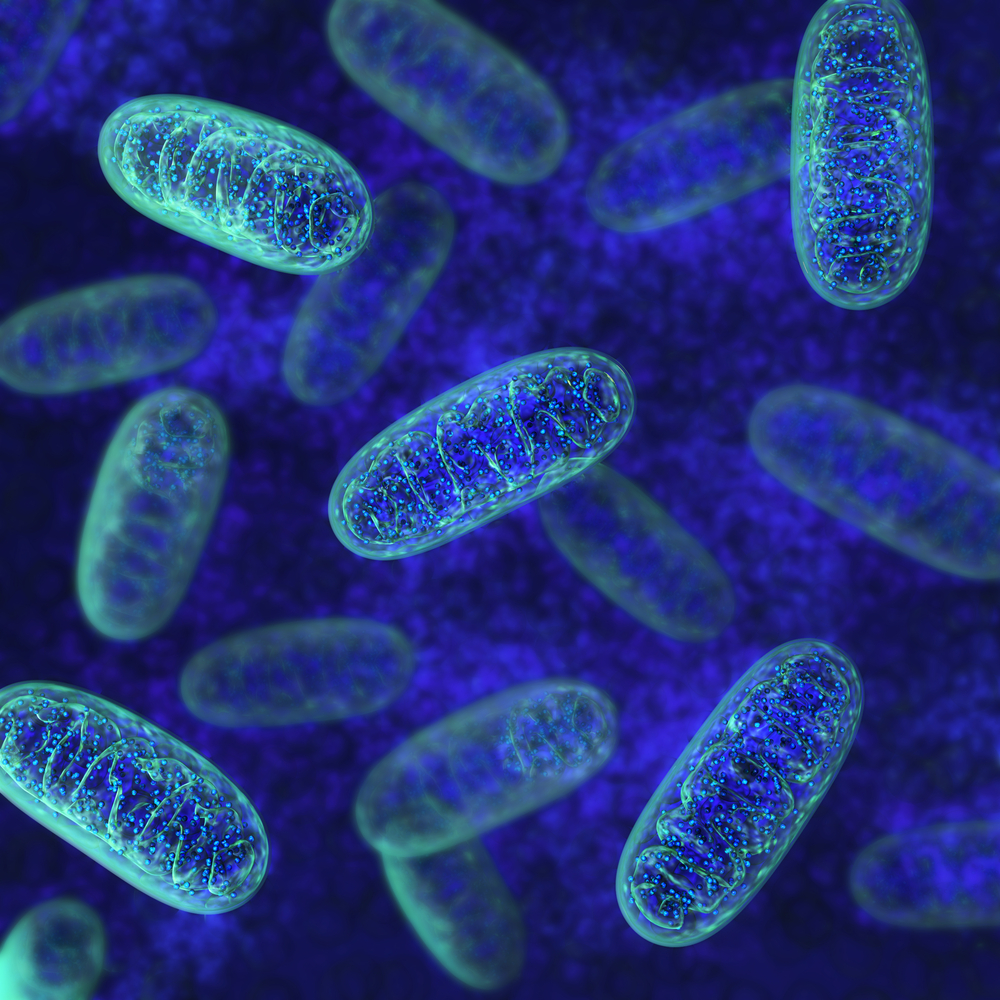

Mitochondria are the parts of the cell that produce energy. Children always inherit their mother’s mitochondrial genome. Mitochondria have their own DNA, different than the DNA in the nucleus. Mutations in either the mitochondrial or the nucleus genome can lead to a broader range of mitochondrial disorders.

“This is not about designer babies and selecting traits,” Philip Yeske, science and alliance officer for the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation, said in a press release. The foundation is concerned about the legislation’s effect on women of childbearing age who have mitochondrial disorders and want to have children. “We don’t feel it’s a slippery slope at all,” he said.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, director of Oregon Health and Science University’s Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy, and his colleagues have shown in animal models that a replacement mitochondrial genome from another mother can be effectively and safely passed to offspring along with the nuclear DNA from the baby’s actual mother.

Mitalipov was working with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to develop plans for human testing of mitochondrial replacement therapies before the bill was approved late last year, effectively halting the research.

The research team proved the “three parent” approach during in vitro fertilization as well, although they did not implant the altered human embryos. The process is described in the article “Towards germline gene therapy ofinherited mitochondrial diseases,” published in Nature in 2013.

The ban is also being questioned by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. An FDA-commissioned expert panel called clinical testing of mitochondrial replacement therapy “ethically permissible” if done under certain conditions.

For the testing to be acceptable, the panel believes that it should only deal with male embryos to ensure the modification is passed only to one generation, and it should be limited to women who are at risk of passing on a mitochondrial disease to their children.

Mitalipov is pushing for policymakers to draw a clearer line between genetic enhancements and genetic corrections, since he believes the two are not equal.

And Yeske said patients may have to go the United Kingdom to have the procedure done, since the British government hasn’t banned mitochondrial testing.