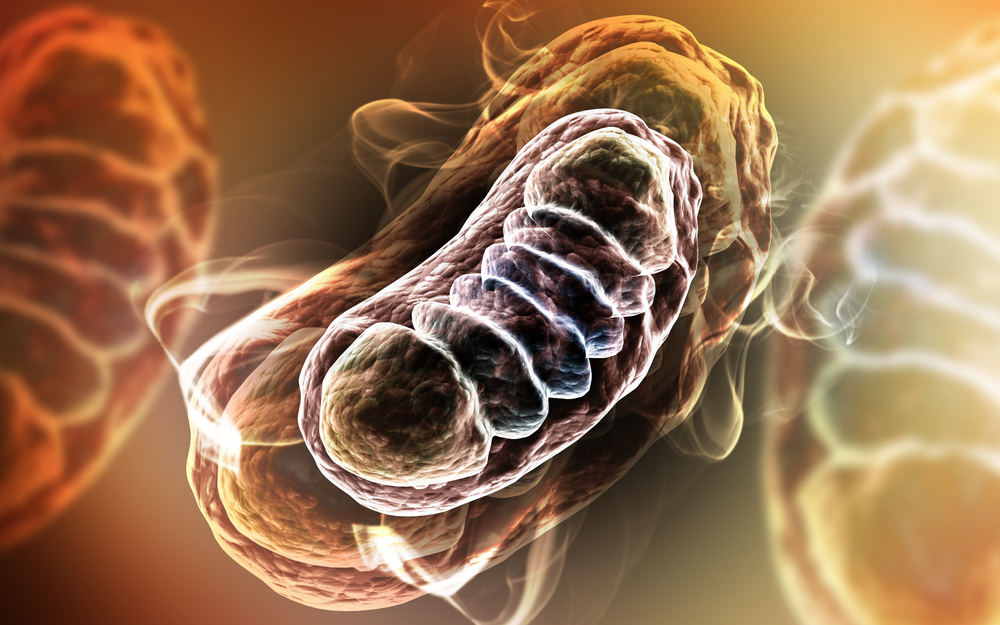

Toxins Crossing the Placental Barrier Can Lead To Mitochondrial Toxcicity, Diseases

A recent controversial decision to legalize “three parent babies” in the United Kingdom has led researchers to believe that they may have found a solution for heading off genetically transferred Mitochondrial Diseases from Mother to fetus. A new study from researchers at the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona in Spain, however, reveals that damage to mitochondria can also be acquired by the fetus through toxins that pass through the placental barrier. The study, entitled, “Mitochondrial Toxicity in Human Pregnancy: An Update on Clinical and Experimental Approaches in the Last 10 Years” was published in the International Journal of Experimental Research and Public Health.

The study sought to expand the data on levels of mitochondrial toxicity found in pregnant women over the span of ten years, and how this toxicity ties in to acquired mitochondrial damage and disease. The research team studied reviews of more than one-hundred different studies available in the Pubmed/MEDLINE database on the subject, in order to identify what types of toxic agents have been found to impact the fetus. Viruses, pesticides, drugs, alcohol and the use of tobacco were all prime examples of toxicity that could potentially transfer from mother to child and damage mitochondria.

[adrotate group=”4″]

“There are many agents which encourage this kind of toxicity,” said Constanza Morén, lead author of the study, in a recent news release. “These include biological agents such as certain viruses, antibiotics, antiretroviral drugs, antipsychotic drugs, gases such as carbon monoxide and chemical substances such as pesticides, alcohol and tobacco, to name but a few.” Morén goes on to explain that factors such as length of exposure and potency affect how serious exposure to these toxins can be for a baby. There is, however, a genetic predisposition to how much toxin passes the placental barrier as well. Depending on the “haplogroup” that defines the particular make-up of a mother’s mitochondria, the ability to block these toxins varies from person to person. These three factors combined make it difficult to understand the general impact of mitochondrial toxicity, since it varies from mother to mother.

The researchers also noted in their study that, while the placenta does indeed filter out most toxins in the bloodstream before entering the fetus, it cannot act as an impenetrable barrier against all toxic substances. Because of this, mitochondrial toxicity can occur at any point from the time of conception until after birth — even up until the end of breastfeeding.

The effects of this toxicity are wide-ranging and can affect both mother and child. The majority of cases in the study were asymptomatic, with only rare cases being serious or fatal. Pregnant women can experience complications such as premature labour, pre-eclampsia, and intrauterine growth restriction as a result of mitochondrial toxicity. For the baby, mitochondrial damage can lead to lipodystrophy, pancreatitis, encephalitis, myopathies or hyperlactatemia and lactic acidosis.

The effects of this toxicity are wide-ranging and can affect both mother and child. The majority of cases in the study were asymptomatic, with only rare cases being serious or fatal. Pregnant women can experience complications such as premature labour, pre-eclampsia, and intrauterine growth restriction as a result of mitochondrial toxicity. For the baby, mitochondrial damage can lead to lipodystrophy, pancreatitis, encephalitis, myopathies or hyperlactatemia and lactic acidosis.

“As the mitochondria participate in vital processes for cell viability and in addition, mitochondria are present in almost all tissues and cell types, if visible clinical manifestations appear they can be observed in almost any organ or tissue,” Morén explained.

The research team concluded that while avoiding toxins during pregnancy is both obvious and paramount, doing so can be more complicated than meets the eye. Environmental, cultural and genetic differences that exist between developed and developing cultures make it difficult to pinpoint what the exposure rate is for pregnant women and how much of the exposure can be avoided: “it is extremely complicated to give an exact figure; we can only assume that there are at-risk populations,” said Morén. “For example, in developed countries, it is estimated that between 10% and 25% of pregnant women smoke, who would be an at-risk group in suffering this type of toxicity, but it does not mean that they all develop it.”

Since smoking along with drug and alcohol consumption, are voluntary, these exposures can be mitigated through education and counseling. However, when environmental exposures are unavoidable, Morén and her team hope to be able to provide mitochondrial toxicity markers in order to help curtail toxic exposure in pregnant women. “Given that prevention is not always possible against accidental or therapeutic exposure, it is essential to identify less toxic substances for the mitochondria, as well as biomarkers (preferably non-invasive) which can give us a clue to its development and facilitate the monitoring of this toxicity during pregnancy.”